Why is Damascus Steel so Expensive?

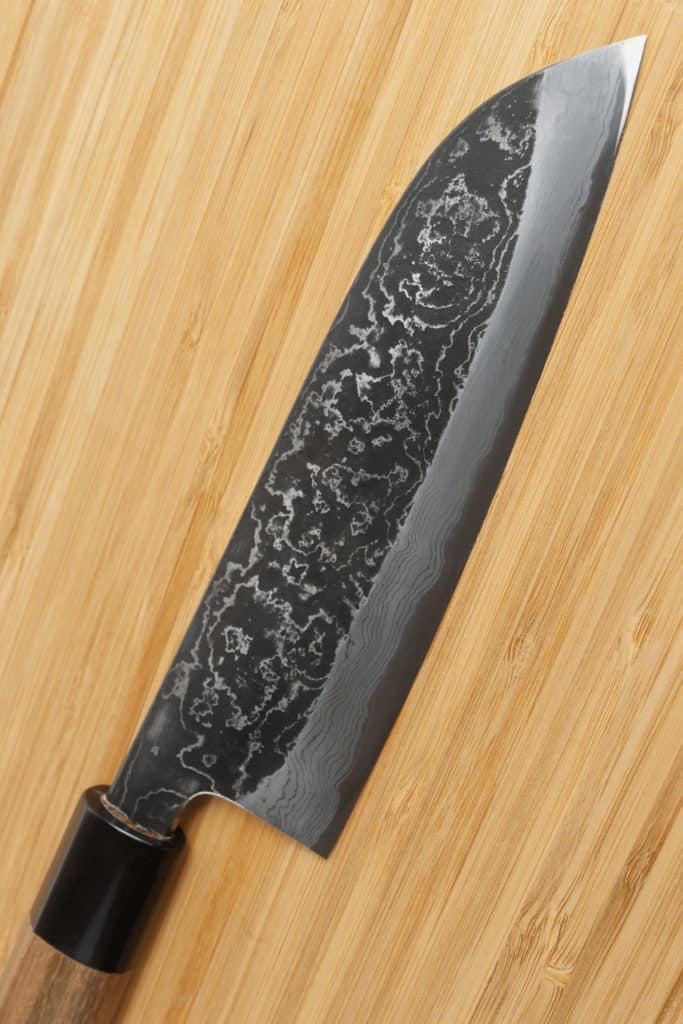

What we know today as ‘Damascus Steel’ is that gorgeous steel embellished with charming watery patterns such as waves, water droplets, and other aqueous designs. These patterns aren’t engraved onto the surface of the metals but result from the way different layers of iron and steel interact with one another during the forging process.

The origins of this kind of steel hark back to the medieval Middle East about 500 AD. The steel is said to have derived from Damascus originally, hence its name, according to Purdue University.

Unfortunately, techniques for producing Damascus Steel as practiced originally by smiths in those far-off days have been lost through the intervening centuries.

Why is Damascus Steel so Expensive?

Damascus steel is so expensive for two reasons. First, because of the unmistakable, unique patterning of Damascus steel which visibly sets it apart from other steels and makes these knives collectible works of art. Second, they have a largely undeserved reputation as superior knives with an especially keen and durable cutting edge. This reputation is based on romanticized historical accounts of the steel’s efficacy.

What the heck is Damascus Steel, and where does it come from?

The origin of the term ‘Damascus Steel’ is disputed. Two Muslim scholars, Ishaq al‑Kindi and Ahmad al‑Biruni, both of whom wrote about swords and the steel used in making swords, wrote extensively about ‘Damascus,’ or ‘Damascene’ swords. They described the names of various swordsmiths and methods of forging, production, geographical location, even the surface appearance of these Damascus steel swords, in so doing, playing a significant role in helping to make the swords famous.

Using al-Biruni’s and al-Kindi’s writings as a source, there are potentially three origins for the term ‘Damascus Steel:’

- Al-Biruni chronicled a famous swordsmith who worked with crucible steel named ‘Damasqui.’

- Al-Kindi wrote about Damascene swords, forged and produced in the city of Damascus, although he was suspiciously and egregiously schtum about the once-seen, never-forgotten pattern in the steel.

- ‘Damas’ in Arabic is the etymological foundation of the word ‘watered.’ This could be related to the egregious water-like pattern that indelibly marks the surface of Damascus Steel swords. This argument is strengthened because Damascus steel is often called ‘watered steel in many languages.’

If you practice a jaundiced eye on the preceding list, you’ll notice I haven’t answered the question, “What is Damascus Steel, and where does it come from?” The reason is simple. We really don’t know.

‘Authentic’ Damascus steel vs. modern Damascus Steel

Most modern Damascus steel is made through ‘pattern welding,’ a technique that was largely abandoned during the 16th century before it was revived in 1973 by a gentleman named Bill Moran, a famed knifemaker. Pattern welding entails subjecting a metal consisting of at least two steel alloys to a process of repeated hammer forging and folding until the metal achieves its characteristic watery patterning.

In the days of yore, Damascus was appreciated for its strength and flexibility, particularly in longer blades (for example, in swords and the like). Today’s contemporary ‘super steels’ easily surpass pattern-welded Damascenes in those two characteristics; strength and flexibility and even the ability to maintain sharpness. However, no one would dispute the sheer aesthetic beauty of Damascus steel over ordinary steel.

Modern Damascus Steel

The true origins of the steel we call today ‘Damascus Steel’ is popularly thought to have come from one of the cities in Syria’s capital, Damascus, the largest city in the old Levant. The term might refer to the wavy patterns which traditionally marked the steel or perhaps refer to the fact that the steel was made or sold in Damascus. If it is for this latter reason, then it would be highly reminiscent of the way Damask textiles are also named after the city of Damascus.

For entirely clear reasons, the original method of making Damascus steel seems to have lasted until the 1700s, when the technique completely disappeared and has thus far eluded all attempts at its recovery. This means that anyone who is today claiming to have a Damascus steel knife is actually speaking about a blade made from steel forged using a modern manufacturing method and is not speaking about a knife made from original Damascus steel.

The original forging method of making this steel was with wootz, a form of steel first made in India more than two thousand years ago. It is known that weapons and other products constructed from wootz enjoyed a surge in popularity during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD in and around Syria, particularly in the city of Damascus.

Forging Damascus steel

Several folks have tried reverse engineering Damascus steel for decades to reveal the secret of its original manufacturing methodology to faithfully reproduce the steel. However, the Damascene metal stubbornly refuses to give up the mystery, and nobody has been able to successfully forge the same material.

The ancient process of making the steel was to melt charcoal, steel, and iron together in a low-oxygen atmosphere, creating wootz. With continued heating, the wootz would absorb some of the charcoal’s carbon, and in the process of slowly cooling the steel alloy, the metal would metamorphize into a rigorously bonded material that contained carbide.

Composing wootz into swords and sundry other weapons led to the development of Damascus steel. The products of this method were available only to the societal elite as forging the steel required a high degree of skill and competence to keep the kiln at a constant temperature, which is the only way that the steel with the famous wavy patterns could be produced.

Frequently Asked Questions About Why is Damascus Steel so Expensive

Why does my Damascus steel knife rust?

Damascus steel knives are constructed of alloys with high carbon content, meaning that the blade has a natural inclination to rust if you do not oil it regularly. Damascus steel knives will also oxidize if kept in leather sheaths because tannins in the sheath will leach out and corrode the steel.

Would engraving damage my knife?

Too many engravings will degrade the blade, of course. On the other hand, engravings which are sure to not spoil the knife will be quite small and really hard to read, making nonsense out of the entire effort. To be honest, the splendor of Damascus steel is in its natural, unadulterated beauty. ‘Gilding the lily’ by engraving your knife is at best a futile gesture and, at worst, a damaging one.

Which modern steel knives compare to Damascus Steel knives?

Metallurgy has come a long way since Damascus Steel was first invented. However, other knives forged with modern steels and which have collected similar levels of fandom are knives from the likes of Victorinox®, Chicago Cutlery®, Shun®, and many others.

Afterword: Why is Damascus steel so expensive?

The two outstanding features of Damascus steel knives are the unique, distinctive wave-like pattern on the blade that is really an unintended consequence of the techniques used in production.

An indelible mark identifies the blade as Damascus steel, but no one has ever found any non-aesthetic significance for the patterns. The second feature is Damascus steel’s supposed shatterproof property, enabling knives made of the material to maintain sharp edges despite suffering repeated blows.

If true, such a feature would be essential in weaponry such as swords, but its usefulness is less evident in a mere kitchen utensil.